Transparency from Anthony Mormile on Vimeo.

Monday, May 12, 2014

"Transparency" Watch the Full Movie

Last summer I helped crew on my friend Anthony Mormile's film Transparency. If you have been following my blog, you may have seen the film already when I posted about the film being available for a limited time. However, the film is now available to watch in it's entirety, when ever you'd like. So if you haven't seen it or would just like to watch the film again, here it is. Enjoy.

Transparency from Anthony Mormile on Vimeo.

Transparency from Anthony Mormile on Vimeo.

Tuesday, May 6, 2014

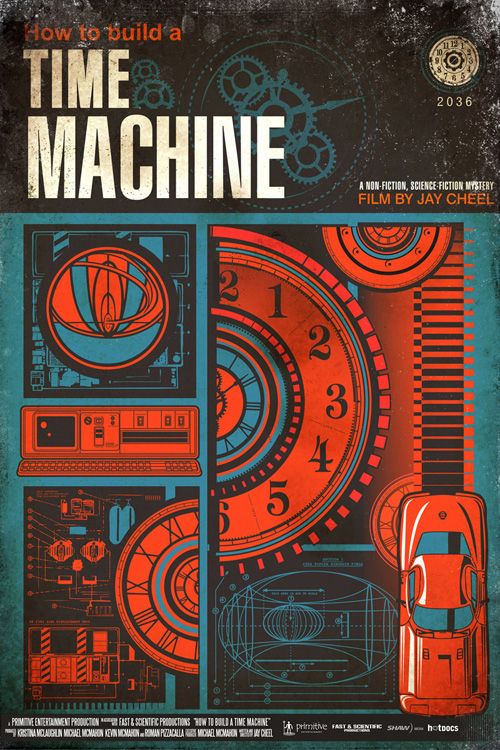

"How to Build a Time Machine" Trailer

How to Build a Time Machine has been one of my most anticipated films since director Jay Cheel first announced it. It's his follow up to his 2011 film Beauty Day, which if you haven't seen, you should go onto Hulu and watch it right now.

As the production took off, it seems there has been some changes to the film's focus from it's original ideas. That is precisely why I love documentaries, how the journey ends can't be known until you reach it.

Now that a trailer is here, I can say that I'm even more jazzed to How to Build a Time Machine. From the trailer, I get the idea that it will be a compelling look into obsession, nostalgia, and mental acquisitiveness. For more updates on the film you can like it on it's Official Facebook Page. I hope you all enjoy the trailer as much as I did.

How to Build a Time Machine - Teaser from Jay Cheel on Vimeo.

Sunday, May 4, 2014

"Rashomon" and the Truth

An essay I wrote about Akira Kurosawa's murder mystery Rashomon. Enjoy.

Japanese master Akira Kurosawa released two films in the year 1950, Scandal and Rashomon. While both films are brilliant in their own respects, it is the latter of the two that achieved international acclaim and introduced Japanese cinema to the western world. Like many of his films, Rashomon explores the moral integrity of individuals and asks difficult questions about the nature of human behavior. In Rashomon, Kurosawa brilliantly constructs a non-linear narrative that is never once convoluted and shows the audience through the use of visuals that the truth told by humans is never objective.

In the film, an event is depicted through the use of flashbacks from the perspectives of four individuals. The first individual to tell his version of the events that took place is the bandit Tajômaru, played by frequent Kurosawa collaborator Toshirô Mifune. As Tajômaru recites his memories of what happened, the camera shows the audience the events unfold from his perspective. After drinking some water that makes Tajômaru feel sick, he decides to go rest by a tree in the forest. He is awakened by two people passing by: a samurai walking side by side with his wife, who sits gracefully atop a horse, her face hidden by a veil. The viewers attention is directed to what Tajômaru sees and is focused on the camera cutting from a close up of his eyes looking camera right to a close up of the woman's feet hanging from the horse. This shot is then quickly followed by the camera slowly panning up to her face. As the flashback of events continues, a pattern of editing is developed, cutting from close ups of Tajômaru's eyes to what he sees. At one point we see in the same shot the samurai and woman pass Tajômaru leaning against the tree, and the camera's motion tracks with the direction he turns his head as he watches them walk away. Through both the use of camera movement and editing, viewers are able to see events unfold from the perspective of the characters.

The ways in which the characters relate and relay an experience directly correlates with how they view themselves. Kurosawa frames the shots of the different characters flashbacks to match their disposition, revealing this to the audience through his artistic vision. The bandit Tajômaru is introduced as a haughty and prideful man. It is by no mistake that Kurosawa chose to open his flashback with an ultra expansive wide-shot of him riding bravely across the screen on the horse he has stolen. The width of the shot can be clearly linked to the character's own expansive ego. When the camera isn't directing the viewer to what Tajômaru is seeing, he is shown looking very masculine in medium and long shots, demonstrating to the audience how a person like him would imagine themselves. When the other character's recall their version of what happened, Kurosawa implements this same techniques to represent their own ego or lack thereof. Kurosawa is revealing to the audience the characters’ true personas.

The direction of the performances play a role in showing the subjectivity of the truth as told by the characters. As each person recalls the events, the performances and behavior of each character involved changes based on who is telling the events. In Tajômaru's rendition of what happened, his own inflated view of himself contributes to a very stylized performance rather than a naturalistic one. Because preserving his ego is more important to him than getting to the actual truth of what happened, his views are skewed. In his telling of the story, his performance shows him as brave and cunning while the woman is weak and the samurai is gullible. If the performances were more natural these attributes may have still been there, albeit not as overtly shown. In Tajômaru's telling it is with ease that he tricks and overcomes the samurai, and the samurai's wife is not as resistant to his sexual advances. Had Kurosawa made the film in which the audience watches the events unfold first hand, he may have chosen to direct the performances in a more natural approach. However having over-emphasized stylistic performances, the overall theme of the film is underlined: the truth as told by humans is subjective.

If one were to ask three different people who witnessed the same event to recall what they saw, they will invariably tell a different story. How humans see themselves and each other affects their perception of the world around them. Akira Kurosawa uses this idea when approaching the narrative for Rashomon, one of the most influential films of all time. The cleverly framed unreliable narration shows the same events four different times, but from a different character's perspective. Through the use of visuals, Kurosawa explores the subjectivity of truth and the individual’s tendency to lie in order to make himself appear better than he really is.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)